- Home

- Archival Material

- College History Projects

- Subject-Based Digital Projects

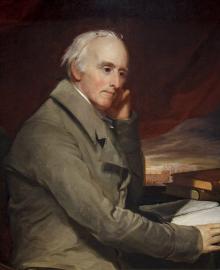

Benjamin Rush (1745-1813)

Benjamin Rush was born to John and Susanna Harvey Rush on December 24, 1745. The family, which included seven children, lived on a plantation in Byberry, near Philadelphia. When Benjamin was five his father died, leaving his mother to care for the large family. At age eight the young boy was sent to live with an aunt and uncle so as to receive a proper education; he went on to study at the University of New Jersey (now Princeton) and received his bachelor's degree from that institution in 1760. Upon returning to Philadelphia, Rush studied medicine under Dr. John Redman from 1761 until 1766, at which time he departed for Scotland to finish his studies at the University of Edinburgh. Receiving his medical degree in June 1768, Rush traveled on to London to further his training at St. Thomas's Hospital; it was in London that Rush first encountered Benjamin Franklin.

Rush returned to Philadelphia in 1769 and started practicing medicine while also serving as the professor of chemistry at the College of Philadelphia. He wrote treatises on medical procedure, politics, and abolition, helping to found the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. His writings on the crisis brewing between the colonies and Britain brought him into associations with such leaders as John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Thomas Paine. At the outbreak of war, Rush joined the continental army as a surgeon and physician.

In June 1776, he was appointed to the Provincial Conference and then to the Continental Congress a month later and signed the Declaration of Independence. Returning to the war effort, Rush was appointed Surgeon-General of the continental army in April 1777; he did not remain so for long, however. He was appalled by the deplorable conditions in which he found the medical service, and consequently became embroiled with George Washington and one of his old teachers, Dr. William Shippen, in accusations of poor management. When Washington and Congress sided with the older Shippen, Rush resigned his commission in protest; the incident led him to express his doubts about the commander-in-chief in a letter to Patrick Henry, which found its way back to Washington, thus ending Rush's military career.

Rush returned to his practice in Philadelphia in 1778. Two years later he began to lecture at the new University of the State of Pennsylvania. He continued to write prolifically on the subject of medicine and medical practice, developing a reputation as a man of literature as well as medicine. In 1783, Rush joined the staff of the Pennsylvania Hospital and actively served until his death. While teaching at the University and serving at the Hospital, Rush furthered his republican ideas regarding universal education and health care; he advocated prison reform, the abolition of slavery and capital punishment, temperance, and better treatment of mental illness. He also believed in creating a better system of schools on every level so that all children, girls as well as boys, could receive the benefits of a proper education that consisted of lower schools as well as colleges; his dream included a national university. It was this idealistic view of education that prompted Rush to envision a college in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, then the edge of the frontier, as the first building block of this great system. Learning of the trustees' plan to expand the Carlisle Grammar School into an academy, Rush gained the confidence of one of them, Colonel John Montgomery, and proceeded to convince the other eight trustees that a college was the better idea. Rush succeeded in garnering support from John Dickinson, then president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania; as a tribute to Dickinson's accomplishments (and donations), the college was named in honor of the great statesman. Rush served as one of the most influential trustees of the College from its founding until his death.

Through his medical practice, lectures, and various writings, Rush gained the reputation as one of the leading physicians and medical theorists in the new nation; he was a pioneer in physiology and psychiatry. For better or for worse, Rush solidified this reputation through his role in the terrible yellow fever epidemic that swept Philadelphia in 1793. He remained in the city and tended to the thousands stricken with the disease, utilizing his practice of "depleting" (i.e. bleeding, purging). Although thoroughly schooled in "nosology," the principle that humors and solids controlled the health of a person, Rush firmly believed that diseases resulted from over- or under-stimulation of the nervous system, to which remedies of depletion or stimulation were to be applied accordingly. Unfortunately for Rush (and for his patients as well), depletion more often than not removed too much blood from the body, ending in death. As a consequence, his theories were condemned by his critics as dangerous and overzealous; although Rush's procedures did sometimes seem to work, he had not gathered enough solid data to justify his practice, and his critics had the mortality statistics to prove their claims. Undaunted, he would continue to write and lecture passionately on his system for the rest of his life.

He had briefly reentered the realm of politics in 1787 to advocate the ratification of the federal constitution; his actions led to an appointment to the ratifying convention for the state. Two years later, along with fellow Dickinson trustee James Wilson he helped to secure a less radical and more effective constitution. As a result of Rush's lifelong patriotism and commitment to the American cause, President John Adams appointed him treasurer of the United States Mint, a post he occupied from 1797 until his death. Meanwhile in 1803 he had become president of the abolition society he had helped to establish, as well as joining the Philadelphia College of Physicians.

On January 11, 1776, Rush married Julia Stockton, the eldest daughter of Richard Stockton of Princeton (and fellow signer of the Declaration). The couple had thirteen children, nine of whom would survive their father. Benjamin Rush died rather suddenly at his home on April 19, 1813 at the age of 67 and was buried at Christ's Church in Philadelphia.

Image Source: Thomas Sully's portrait of Benjamin Rush. Photograph by Carl Sander Socolow

Date of Post:

2005

College Relationship:

Trustee - Years of Service:

1783-1813