- Home

- Archival Material

- College History Projects

- Subject-Based Digital Projects

Butler's Analogy

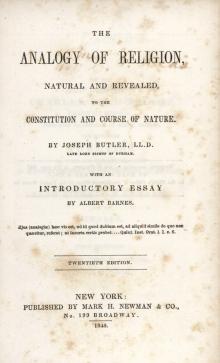

Joseph Butler (1692-1752) wrote his infamous Analogy of Religion, Natural and Revealed, to the Constitution and Course of Nature, in 1736. Butler was born and educated in England as a Presbyterian but became ordained in the Church of England in 1718, and eventually became the Dean of St. Paul's Cathedral and later Bishop of Durham. He studied Locke, Shaftesbury, and Hutcheson, philosophers who all influenced his writing. In his Analogy, Joseph Butler discusses his views on morality, and how under normal circumstances, humans are designed to follow moral lives. The work impressed Hume and Wesley and became widely read first in Scotland during the end of the eighteenth century, and made its way to Oxford, and eventually spread to American universities and colleges during the early part of the nineteenth century when many such institutions were heavily influenced by Scottish philosophy. Dr. Benjamin Rush, one of Dickinson's founders, who was educated at Edinburgh University, certainly read the Analogy when, following a long career to the study of medicine and science, he began later in life to search for a unity between nature and God. He found some answers to his questions in Butler's Analogy.

The Analogy first became part of the College curriculum in 1834, when Dickinson reopened under the presidency of John Price Durbin. This was in keeping with a current extensive drive in the Methodist Church to support and purify American higher education. On March 12, 1833, the remaining members of the board of trustees of the previously Presbyterian affiliated institution received an inquiry from members of the Baltimore Conference of the Methodists, under the leadership of Reverend Edwin Dorsey, asking whether they would consider resigning and permitting the Conference to take control of the College. After almost three months of debate, the old board of trustees resigned on June 6, 1833. The new Methodist regime began the next day with the election of Durbin as president.

Durbin immediately set out to revamp the academic program of the College, and established a new curriculum that required student to engage in courses in religion and ethics, along with setting out a clear guideline of the different academic courses of the time. It was required that all second semester seniors study Butler's Analogy in their English courses, as until 1840, all religion classes were offered through the English faculty. Because Butler was taught in their last semester, it often became the subject of orations or oral interrogations, held publicly at the end of each Dickinson student's career, and required for graduation. As one would imagine, the Analogy quickly gained much notoriety as a terror to seniors.

Under the leadership of a strong president, any opposition that students felt towards the Analogy was kept at under control until 1848 with the appointment of a new president, Jesse Truesdell Peck. President Peck had never himself attended College and proved to be a weak leader who received little respect from the students. As a result, Peck fell mercy to the brutality of student jokes and pranks. One of these famous incidents involved the hated Analogy directly. The faculty meeting minutes of the College tell how one night in late September of 1850, a group of students buried a copy of Butler in full ceremony, accompanied by much noise, lighting, and firing of pistols. Peck punished the students involved, but only by scolding them in a public meeting, where he reprimanded them for their rude behavior of “boisterous hallooing, the firing of pistols, ringing of the bell, and thus disturbing families, exciting public resentment and bringing odium upon the college.” The following year, Peck was to admit final defeat and resign as President.

Despite this display of disapproval, Butler's Analogy continued to haunt seniors for forty-five more years. Its overall influence waned at the end of the nineteenth century after it fell under the eye of critics like Leslie Stephen and last appears in student catalogues at Dickinson in 1895-96 academic year. The College Archives and Special Collections contain Charles Ford Reed's personal copy of the Analogy; Reed was an alumni who graduated in 1851 and as a member of the senior class who tried to banish the terror of this book from their lives by interment.

Date of Post:

2005